What Comes After The Trans Pacific Partnership (TPP)?

The President formally withdrew the United States from the TPP on January 23. Because the United States represents over 60% of the combined GDP of the original 12 countries, without U.S. participation the agreement cannot enter into force.

The TPP was the largest regional trade accord in history and would have set new terms for trade and business investment among the United States and 11 other Pacific Rim nations, representing 40 percent of global GDP and one-third of world trade. Six (6) countries have existing Free Trade Agreements (FTA) with the United States (i.e., Singapore, Chile, Australia, Peru, Mexico, and Canada) and, five (5) have no FTA (i.e., Japan, Brunei, New Zealand, Vietnam, and Malaysia).

The President has expressed his preference for bilateral free trade agreements.

UK Prime Minister Theresa May and the President affirmed in a quick, 18-minute news conference following their January 27 meeting that the US and the UK would immediately begin negotiating a bilateral trade agreement.

Reportedly Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe also will discuss a bilateral trade agreement with the President when they meet in February.

US withdrawal from the TPP provides new impetus to negotiations on the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP). The RCEP has been under negotiation since 2013 among the ten (10) member states of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) (Brunei, Burma (Myanmar), Cambodia, Indonesia, Laos, Malaysia, the Philippines, Singapore, Thailand, Vietnam) and India, China, Australia, Japan, South Korea and New Zealand.

What is the Status of the North American Free Trade Agreement (“NAFTA”)?

The status of NAFTA is still to be determined. The President has expressed hostility towards NAFTA, and has indicated that he intends to renegotiate the deal with Canada and Mexico. There is no legal prohibition against any efforts to renegotiate NAFTA, in its entirety or parts of it.

Under H.R. 3450, the North American Free Trade Agreement Implementation Act, Pub. L. No. 103-182 (the “Implementation Act”), the President is not required to obtain Congressional authorization to withdraw the U.S. from NAFTA. As the President-elect has pointed out, NAFTA contains a “withdrawal” provision under Article 2205 which simply says: “A Party may withdraw from this Agreement six months after it provides written notice of withdrawal to the other Parties. If a Party withdraws, the Agreement shall remain in force for the remaining Parties.”

Renegotiation could take months, if not years to hammer out the details of a revised NAFTA. Although there are few details on what the President wants to change, a number of possible objectives include: Revising the rules-of-origin criteria; Modifying the procurement rules for government contracts; and, amending the investor dispute settlement system (i.e. private company suits against a government).

Can The President Impose New Tariffs?

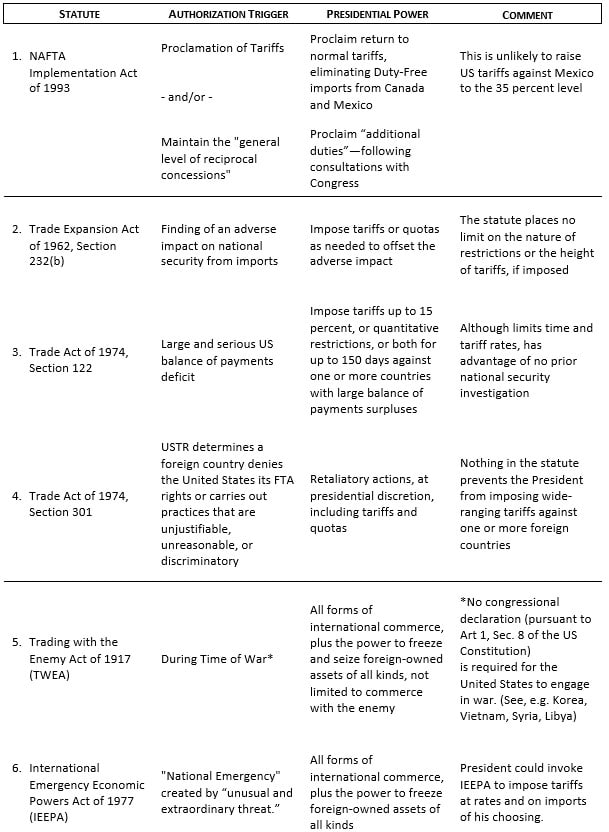

The short answer is “probably.” As with other trade issues, one key consideration is the extent of presidential authority to act unilaterally. The Constitution (Art. I, Sec. 8, cl. 1) gives Congress the power to impose tariffs, but Congress has delegated some of its authority to the President to take trade-related action if he makes a specified threshold determination before taking a trade-related action. The President believes that these existing laws give him sufficient authority to impose tariffs by executive action without seeking new legislation. This argument has some historical precedent and is not without some legal merit.

The following is a summary of Presidential Trade-Related Authority:

The 20% Import Tax

This is Import Tax is not the same as the duty, tax and fees collected by Customs and Border Protection (CBP) at the time of importation. It is included in a sweeping overhaul of the corporate tax system proposed in the Republican blueprint for tax reform, announced in late June, 2016. The proposed “import tax” is intended to counter the advantage enjoyed by America’s trading partners nearly all of whom employ consumption-based value-added taxes (VAT) as a revenue source. The advantage results from zero-rating exports and fully taxing imports. Because the US derives revenues primarily from income taxes, WTO rules make it difficult to implement a similar “border adjustment.”

The proposed tax, commonly referred to as a “border tax adjustment” or “destination-based consumption tax,” would be realized by denying business deductions for imported goods and services and excluding exports of goods and services from the tax base. See the following example:

Suppose the US purchasing firm is not allowed a business deduction for imported parts costing $1,000, but is allowed a deduction equal to 20 percent of the cost for identical domestic parts costing $1,000.

Then the after-tax cost to the purchasing firm of domestic parts is $800, whereas the after-tax cost of imported parts is 25 percent greater, or $1,000.

Likewise, suppose exported goods worth $1,000 are not counted in the US selling firm’s tax base, but the same goods sold domestically are counted in the firm’s tax base. Then after-tax receipts from exports are $1,000, or 25 percent greater than after-tax receipts from domestic sales.

If nothing else changed (most significantly, the dollar exchange rate), the after-tax cost of imports would be 25 percent more than that of equivalent domestic goods and sales, while exports would be 25 percent cheaper.

What approach will the President Take to Sanctions on Russia, Iran, and Cuba?

There is a general expectation that the new administration’s posture toward Russia will relax, while tightening toward Iran and Cuba. During the campaign, the President criticized the Iran nuclear deal and the easing of Cuba sanctions. As President, he has the authority to revisit those policies.

The multilateral Iran deal may prove challenging to unravel. Iran has already received many of the deal’s benefits, reopening business with companies from the European Union and other countries in sectors such as energy (e.g. Royal Dutch Shell and Total) and transportation (e.g. Airbus, Italy’s state railway company, Ferrovie dello Stato (FS), and most recently, Boeing). It could be difficult to persuade other parties such as the EU, China and Russia to re-impose sanctions and, reinstituting unilateral US sanctions might not be deemed effective in deterring the Iranian nuclear program.

On Cuba, the President’s more limited pronouncements seemed to call for the reversal of the Obama administration’s liberalization steps until the Cuban government makes political reforms.

As the new Administration’s priorities become clear, it will be important to identify areas where U.S. sanctions goals veer from those of its allies. Materially conflicting approaches (e.g., between the EU and U.S. approach to Iranian and/or Russian sanctions targets) could create headaches for international corporations and financial institutions struggling to ensure compliance with all the sanctions requirements that are applicable to them and to their customers.

References:

Gary Clyde Hufbauer, Could a President Trump Shackle Imports?, Peterson Inst. For Int’l Economics (Sep. 2016)

Jordan, Manzanares, et. al., NAFTA in a Land of Uncertainty: A US Perspective, Gardere (Jan. 2017)

Caitlain Devereaux Lewis, Presidential Authority over Trade: Imposing Tariffs and Duties, Congressional Research Service R44707 (2016).

Alan J. Auerbach, A Modern Corporate Tax, The Center for American Progress/The Hamilton Project, (2010)

Alan J. Auerbach, Douglas Holtz-Eakin, The Role of Border Adjustments in International Taxation, American Action Forum, (2016)

A Better Way: Our Vision for a Confident America (June, 2016)

Gary Clyde Hufbauer and Zhiyao (Lucy) Lu, Border Tax Adjustments:Assessing Risks and Rewards, Peterson Inst. For Int’l Economics (January 2017)